FOXBORO -- At some point on a perfect spring Monday in New England, Matt Light drove away from Gillette Stadium and into the rest of his life.

He is 33-years-old and the 11-year swath of time in which he lived in a world of maximum physical and mental stimulation is over.

If he lives to the ripe, old age of 80, the NFL career for which he'll always be remembered in the public eye will have represented about 13 percent of his life.

The other 87 percent has been and will be all about Matt Light, normal guy. He seems exceptionally well-positioned to make the transition.

"Everybody has their own way of dealing with things," Light said during a nicely-executed retirement ceremony at the Patriots Hall of Fame. "I'm fairly confident that the transition will happen and it'll go smoothly and things will work out. That's kind of just the way I've led my life. If you surround yourself with quality people, you surround yourself with real people and you do things for the right reasons, opportunities will present themselves to you. And if it's meant to be it'll work out in time."

This is a very important subject right now. Young men who decide or are told that their football careers are over enter civilian life and are faced with figuring out who they are as men, husbands, fathers, sons and members of society as ex-NFL players.

The focus since Junior Seau's suicide last Thursday has been on concussions and CTE and wondering how blows to the head caused him to kill himself.

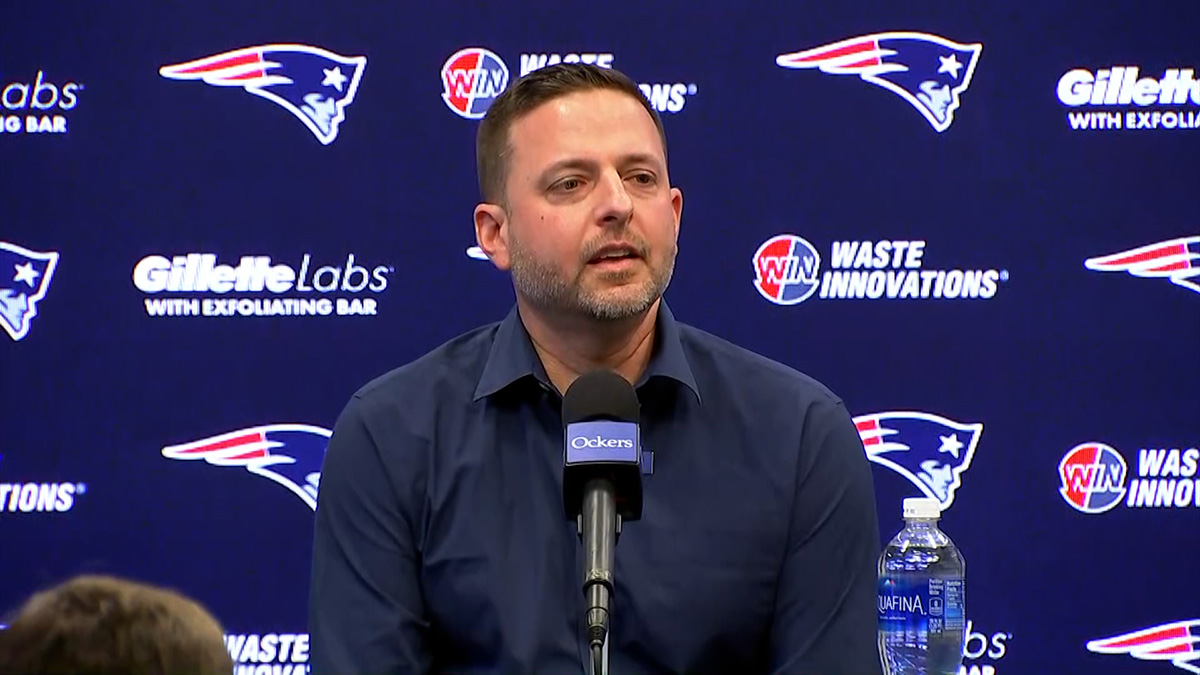

New England Patriots

Far less discussion has been devoted to talking about depression and the transition to post-NFL life that so many players seem to struggle with.

CTE may or may not be found if Seau's brain is donated for evaluation. But depression and a loss of his will to live was certainly present for Seau and any other person who makes the tragic decision he made.

There may be scores of former NFL players with CTE that lived productively and happily for the rest of their lives but we never learned of the damage they had because they didn't die young and violently and have their brains examined.

CTE may or may not be a precursor to suicide. But depression is. And the post-football funk players descend into is what needs addressing.

On Sunday, Bears wide receiver Brandon Marshall, who is bipolar and struggles with mental health issues, wrote a piece for the Chicago Sun-Times:

Looking at the situation with Seau and other cases with retired athletes, I think our focus should be more on why the transition seems to be so hard after football.As athletes, we go through life getting praised and worshipped and making a lot of money. Our worlds and everything in themspouses, kids, family, religion and friendsrevolve around us. We create a world where our sport is our life and makes us who we are.When the game is taken away from us or when we stop playing, the shock of not hearing the praise or receiving the big bucks often turns out to be devastating. The blueprint I am creating for myself will help not only other athletes, it will help suffering people all over."London Fletcher said post-career counseling should be mandated and he wants the NFL and the NFLPA to work together on that.

You take the decision out of guys hands, and that way, maybe some of them will be helped, Fletcher told Peter King of Sports Illustrated. If players have to go seek counseling on their own, lots of guys wont do that. Men in general, were wired to hold things inside. Its not manly to be vulnerable and ask for help. For me, now, I can tell you Im going to seek help if I feel I need it. Thats what Juniors death has taught me.

When a player's NFL career ends, his prime earning years are over. The vocation he's devoted himself to for decades is gone. He's got about 60 years of life staring him in the face and a family to re-introduce himself to, a family that has to itself adjust to the fact that the lights have gone off on a way of life they may have also strongly identified with.

It's hard. Some make the transition easily. Others do not.

The help is there for players who seek it, said Light.

"The resources and the people that are in place within the NFL and the NFLPA and for a large part with each individual organization can really help guys with that transition," Light explained. "It's been helpful to me to have a guy like (strength coach and player development person) Harold Nash who says, 'Hey, here's some things the NFL offers or the PA offers and here's what you need to take advantage of and then going out and taking advantage of those things.' Those have been very helpful to me whether it's an entrepreneurial course or a broadcast boot camp, whether its getting involved in community affairs or anything of that nature.

"The more that you extend yourself beyond the football world and get involved with your community and the people that make up the community and make that commitment to do things outside of football (the better)," said Light. "Hopefully that will serve me well."

In August of 2006, Junior Seau announced his retirement saying, "Im not retiring. I am graduating. Today is my graduation day. Retirement means that youll just go ahead and live on your laurels and surf all day in Oceanside. It aint going to happen."

But he had no mental picture of what life without football would look like. He wasn't ready to leave and -- four days later -- he signed with the Patriots and played until he was 40. And even then, the transition was ultimately impossible to endure.

We grow to care about these men. That some feel they have landed in life's discard pile before their hair has turned gray is as chilling as anything that shows up on a microscope slide in some laboratory.

On Monday, Light said, "When I finally close a chapter, I don't look back."

A clean break. And a new book. One with a happy ending. That's what we should all hope these men find.